A Framework to Address Maternal and Child Health Inequities as a Place-Based Issue

Tonni Oberly, Jason Reece, & Leigh Graham

Abstract

Maternal and child health inequities are a key indicator for community health and wellbeing. Black communities are especially burdened with unjust maternal and infant mortality. These outcomes are upheld by place-based factors known as the social and structural determinants of health, including structural racism. While attention to inequitable MCH outcomes has grown, the authors argue that MCH should be addressed as a place-based issue. With this, we demonstrate the utility of translating the individual-level Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA) Holistic Care Principles to the community level. This approach is akin to other Black-led planning paradigms and can lead to further reintegrating the fields of public health and city planning.

Introduction

Maternal and child health (MCH) outcomes are a key indicator for community health and especially highlight deficits in how communities care for their most marginalized populations.1 Consider Guinier’s canary in the coal mine analogy for political-race:

"The canary is a source of information for all who care about the atmosphere in the mines—and a source of motivation for changing the mines to make them safer. The canary serves both a diagnostic and innovative function. It offers us more than a critique of the way social goods are distributed. What the canary lets us see are the hierarchical arrangements of power and privilege that have naturalized this unequal distribution."2

Importantly, the problem does not lie within the canary; the problem is the coal mine, the detrimental environment. With the growing recognition of the impact of place on health outcomes in public health,3,4and likewise the role of health in fostering livable communities in urban planning practice, both fields must further address MCH as a place-based issue. In this essay, we demonstrate the utility of scaling a framework developed by the Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA) research working group from an individual care model to a place-based approach that offers a path forward for public health and urban planning practitioners and scholars to address community inequities through a focus on MCH inequities.

Racial inequities in MCH

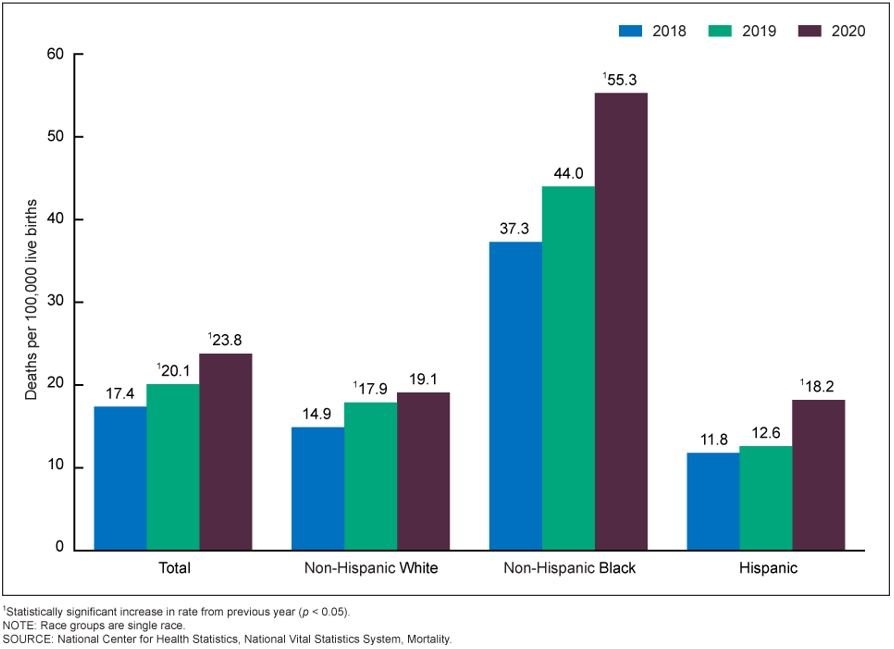

We hear Guinier’s canary singing when we look at the persistent racial inequities in childbirth in the US: Infants born to Black birthing people are more than twice as likely to die before their first birthday compared to infants with non-Hispanic white mothers.5 Wide inequities in maternal mortality between non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic birthing people are persistent and increasing (Image 1).6 Maternal mortality in the United States has been rising since 2010, making the U.S. an outlier among high-income countries.7 Notably, only 35% of maternal deaths occur during childbirth and in the immediate days following. The remaining two-thirds occur during pregnancy and in the first year post-partum,8 as negative structural determinants of health including racism, poverty, gaps in healthcare access, community and interpersonal violence, and other factors put birthing people’s lives in jeopardy.9 These indicators are another measure of the racism that permeates all aspects of life in the United States including access to housing, education, transportation, healthful food, quality clinical care, and disaster preparedness and upholds the systems that perpetuate inequities in MCH outcomes.9-14 These disturbing trends have generated longstanding and newfound concern15,16 and long overdue policy action.17,18

Image 1: U.S. Maternal Mortality Rates by Race 2018-2020

In the US, public health and urban planning are sister fields with joint origins in urbanization and industrialization19 that, after carving out parallel paths for community improvement over the 20th century, are again reintegrating over shared interests in sustainable, healthy communities. Yet, maternal health is mostly overlooked in planning practice (see Reece,20 for a notable exception), and public health responses to maternal health overly focus on the individual and mother-child dyad instead of structural factors such as access to quality education, housing, food, and transportation.

Due to the intersectional and nested nature of the factors contributing to MCH inequities, the authors suggest an interdisciplinary approach that spans planning and public health, and centers feminist epistemology to address these deeply entrenched inequities. The authors leverage the "Best Practices for the Conduct of Research With, For, and By Black Mamas" developed by the BMMA research working group.15 While the unit of care of the BMMA framework is the individual patient, we scale these principles to the community level through city and regional planning theory and practice.

Learning from Black Mamas: Holistic Research and Practice for Healthy Communities

The BMMA’s best practices start with the recognition of the intersectional impacts of historic and current systems of oppression, including racism and sexism. Although acknowledgement of historical structures of oppression is growing in public health and planning,4,21,22 a gap remains in moving from scholarly attention to practical action, and participatory or collaborative approaches to research are still frequently discounted as less rigorous.23

The working group establishes three truths that underpin their work:

- There are no solutions or interventions to improve MCH outcomes for Black birthing people that they do not already possess.

- “Shame and blame” narratives are racist and harmful.

- Separating the social determinants of health from clinical determinants of health is unethical and problematic.24

These truths demand a recognition of the structural and systemic factors that contribute to inequitable outcomes rather than an individualistic understanding of health. Guided by these position statements, the BMMA working group’s best practices connect theory and practice to create an actionable framework of holistic care principles that center Black birthing people’s experiences. We demonstrate the translation of the BMMA care principles to the community-level to address MCH inequities as a place-based issue in Table 1 below.

The BMMA framework is a trauma-informed care approach. This means it understands trauma as a community health issue rather than solely an individual’s health burden. Trauma-informed planning recognizes communal trauma, stemming from historic and structural conditions of racism, sexism, disenfranchisement, and isolation.25 Examples of trauma informed planning practice include acknowledging harm done and promoting consciousness, honoring history and celebrating culture, fostering social cohesion, removing participation barriers, and promoting safety.25 By integrating the principles and practices of trauma-informed care, planners can more holistically uplift and meet the needs of Black birthing people and Black communities.

The principles of holistic care outlined by BMMA should guide planning and public health theory and practice to improve maternal and child health in Black communities. Black-led community-based doulas are perhaps one of the best aligned, evidence-based interventions with the community principles outlined.26 Similarly, the foundational strategies of Best Babies Zones which take a place-based, community-driven approach to drive a social movement harkens to the holistic approach needed to improve birth outcomes.27 Housing mobility programs which provide financial and social support to enable families to move to areas of opportunity such as Central Ohio’s Move To Prosper could be further enhanced by centering the highlighted principles.28 For example, while Move To Prosper provides wrap-around services to individual families, community needs are not addressed.

Joining Otherwise Black-led Planning Paradigms for Healthier Communities

Venerable planning paradigms spanning from advocacy29 and equity planning30 to communicative planning31 have failed to shift power and agency to Black communities. Our framework joins “otherwise” planning paradigms that critique and counter conventional planning theory by centering Black communities.32 Similarly, Robert’s Critical Sankofa planning recognizes alternative modes of knowledge such as collective memory, cultural performance, and oral tradition to uncover unrecognized historical wisdom that can be applied to shape the future.32 Expanding the BMMA working group’s framework to the community-level provides opportunities to imagine new spatial and communal Black futures with wellbeing and flourishment as a reality.

Planning and public health should center maternal and child health as a primary outcome for community wellbeing, supporting, enabling and partnering with Black mamas as the experts leading the way forward. Scaling BMMA’s framework to the community level for holistic research and practice for healthy communities is a demonstrable approach that bridges aligned fields interested in community wellbeing without marginalizing or tokenizing lived experience. We have argued that MCH outcomes are an overlooked and underutilized metric for community and societal wellbeing. Metaphorically, MCH inequities, particularly Black birthing people’s higher rates of mortality and morbidity and infant loss, are the canary in the coal mine. Planners and public health practitioners must be reflective in their research and practice with, for, and by Black communities, including birthing people, shifting power in who is driving research and action. The fields must continue to diversify their workforce and prioritize uncovering anti-Blackness endemic in the professions and communities,21 including in so much well-regarded scholarship on community and health inequities that finds correlation or causation with race, rather than racism, thus implicitly blaming Black people for their poor health.33 In doing so, we ask our planning and public health colleagues to consider this: the canary does not only sing songs of despair. We sing songs of joy, love, and community.

About the Authors

Tonni Oberly, MPH is a doctoral candidate in City and Regional Planning at The Ohio State University Knowlton School of Architecture and a Birth Equity Research Scholar at the National Birth Equity Collaborative (NBEC). Oberly's research sits at the intersection of planning and reproductive justice, with a focus on Black maternal and child health outcomes.

Jason Reece, PhD is an associate professor of city and regional planning at the Knowlton School and interim executive director at The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race & Ethnicity. His research seeks to understand the role of city planning in fostering a built and social environment which supports a just city and healthy communities.

Leigh Graham, PhD, MBA is the Senior Advisor for Innovation Research at the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Graham is an expert in neighborhood and racial equity in urban policy and public health, particularly after disasters and in times of crisis.

References

- Barnett K, Reece J. Infant Mortality in Ohio. Kirwan Inst Issue Brief. 2014;16.

- Guinier L, Torres G. The miner’s canary: enlisting race, resisting power, transforming democracy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2002. 392 p.

- Du Bois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro: a social study. Paperback edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1899. 315 p. (The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois).

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017 Apr;389(10077):1453–63.

- Ely D, Driscoll, A. National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 69, Number 7 July 16, 2020, Infant Mortality in the United States, 2018: Data From the Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File. 2020;18.

- Hoyert DL. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020. 2022;5.

- The Commonwealth Fund. Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Primer [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-brief-report/2020/dec/maternal-mortality-united-states-primer

- Petersen EE. Vital Signs : Pregnancy-Related Deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and Strategies for Prevention, 13 States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Nov 11];68. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6818e1.htm

- Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J Womens Health. 2020 Nov 12;jwh.2020.8882.

- Boarnet MG. About This Issue: Planning’s Role in Building Healthy Cities: An Introduction to the Special Issue. J Am Plann Assoc. 2006 Mar 31;72(1):5–9.

- Botchwey ND, Falkenstein R, Levin J, Fisher T, Trowbridge M. The Built Environment and Actual Causes of Death: Promoting an Ecological Approach to Planning and Public Health. J Plan Lit. 2015 Aug;30(3):261–81.

- Wallace M, Crear-Perry J, Richardson L, Tarver M, Theall K. Separate and unequal: Structural racism and infant mortality in the US. Health Place. 2017 May;45:140–4.

- Dyer L, Chambers BD, Crear-Perry J, Theall KP, Wallace M. The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality in Louisiana, 2016–2017. Matern Child Health J [Internet]. 2021 Jun 19 [cited 2021 Jun 29]; Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10995-021-03189-1

- Mehra R, Boyd LM, Ickovics JR. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017 Oct;191:237–50.

- Zambrana RE, Williams DR. The Intellectual Roots Of Current Knowledge On Racism And Health: Relevance To Policy And The National Equity Discourse: Article examines the roots of current knowledge on racism and health and relevance to policy and the national equity discourse. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022 Feb 1;41(2):163–70.

- Martin N, Cillekens E, Freitas A. Lost Mothers [Internet]. ProPublica. 2017 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/lost-mothers-maternal-health-died-childbirth-pregnancy

- “Momnibus” legislation aims to help black moms - ProQuest [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/openview/a0d69564e9936d7b726e2e3fc158ac8b/1?cbl=48920&parentSessionId=%2BDYwaaR0hu4rJ%2F%2BrsZE41o%2BIP1UjQlKQ%2F9tJOO1jZk8%3D&pq-origsite=gscholar&accountid=9783

- Black Maternal Health Momnibus [Internet]. Black Maternal Health Caucus. 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 14]. Available from: https://blackmaternalhealthcaucus-underwood.house.gov/Momnibus

- Corburn J. Reconnecting Urban Planning and Public Health. In: Crane R, Weber R, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2012 [cited 2020 Jul 11]. p. 391–417. Available from: http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195374995.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195374995-e-20

- Reece J. More Than Shelter: Housing for Urban Maternal and Infant Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan;18(7):3331.

- Thomas JM, Ritzdorf M, editors. Urban planning and the African American community: in the shadows. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997. 321 p.

- Goetz EG, Williams RA, Damiano A. Whiteness and Urban Planning. J Am Plann Assoc. 2020 Apr 2;86(2):142–56.

- Warren MR, Calderón J, Kupscznk LA, Squires G, Su C. Is Collaborative, Community-Engaged Scholarship More Rigorous Than Traditional Scholarship? On Advocacy, Bias, and Social Science Research. Urban Educ. 2018 Apr 1;53(4):445–72.

- BMMA Research Working Group. Black Maternal health Research Re-Envisioned: Best Practices for the Conduct of Research With, For, and By Black Mamas [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Mar 21]. Available from: https://harvardlpr.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2020/11/BMMA-Research-Working-Group.pdf

- Falkenburger E, Arena O, Wolin J. Trauma-Informed Community Building and Engagement. 2018;18.

- Kozhimannil KB, Vogelsang CA, Hardeman RR, Prasad S. Disrupting the Pathways of Social Determinants of Health: Doula Support during Pregnancy and Childbirth. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016 May 1;29(3):308–17.

- Pies C, Barr M, Strouse C, Kotelchuck M. Growing a Best Babies Zone: Lessons Learned from the Pilot Phase of a Multi-Sector, Place-Based Initiative to Reduce Infant Mortality. Matern Child Health J. 2016 May;20(5):968–73.

- “Going Local to Support Fair Housing: Establishing the Move to PROSPER Housing Mobility Program” by Jason Reece, Rachel Kleit & Amy Klaben (January-April 2019 P&R Issue) [Internet]. PRRAC — Connecting Research to Advocacy. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://prrac.org/going-local-to-support-fair-housing-establishing-the-move-to-prosper-housing-mobility-program-january-april-2019-pr-issue/

- Davidoff P. ADVOCACY AND PLURALISM IN PLANNING. J Am Inst Plann. 1965 Nov;31(4):331–8.

- Krumholz N. Urban Planning, Equity Planning, and Racial Justice. In: Thomas JM, Ritzdorf M, editors. Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997.

- Sager T. Reviving critical planning theory: dealing with pressure, neo-liberalism, and responsibility in communicative planning. New York: Routledge; 2012. 328 p.

- Bates LK, Towne SA, Jordan CP, Lelliott KL, Bates LK, Towne SA, et al. Race and Spatial Imaginary: Planning Otherwise/Introduction: What Shakes Loose When We Imagine Otherwise/She Made the Vision True: A Journey Toward Recognition and Belonging/Isha Black or Isha White? Racial Identity and Spatial Development in Warren County, NC/Colonial City Design Lives Here: Questioning Planning Education’s Dominant Imaginaries/Say Its Name – Planning Is the White Spatial Imaginary, or Reading McKittrick and Woods as Planning Text/Wakanda! Take the Wheel! Visions of a Black Green City/If I Built the World, Imagine That: Reflecting on World Building Practices in Black Los Angeles/Is Honolulu a Hawaiian Place? Decolonizing Cities and the Redefinition of Spatial Legitimacy/Interpretations & Imaginaries: Toward an Instrumental Black Planning History. Plan Theory Pract. 2018 Mar 15;19(2):254–88.

- Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On Racism: A New Standard For Publishing On Racial Health Inequities | Health Affairs [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347/

HHPR Senior Editor Layla Chaaraoui interviewed Dr. Sarah Naomi Bleich, PhD. Dr. Bleich is a Professor of Public Health Policy at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health in the Department of Health Policy and Management and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Dr. Bleich’s research focuses on obesity prevention and diet-related diseases. She is currently working on projects relating to COVID-19’s implications on food and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Her work has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the British Medical Journal, Health Affairs, and the American Journal of Public Health. She has held a number of positions, including a Senior Policy Advisor to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Vice Provost for Special Projects at Harvard University. Dr. Bleich earned her BA degree from Columbia University in Psychology and her PhD from Harvard University in Health Policy.